“If men do not comprehend the nature of God, they do not comprehend themselves.”

– Joseph Smith

MONOTHEISTS CARRY GOD AROUND IN THEIR POCKET like a Swiss Army knife. He must be suited to every need, equipped for every challenge. Increasingly multi-functional with each generation, He has become the Nail File, Cork-Screw, and Letter-Opener of our lives. Need a Plastic Toothpick? The newest model comes with that. Thumb-Drive? It’s got that, too. Appurtenances aplenty.

Perhaps we do the same thing when we imbue our single God with such a profusion of personality traits. Need benevolent and caring? The Lord is my Shepherd. Eager for your enemies to get their comeuppance? Mine Eyes Have Seen the Glory.

The Judeo-Christian accounts of God’s dealings with humankind present a perplexing case study in Multiple Personality Disorder. For each admirable trait on display, we find its opposite: long-suffering and short-fused; judicious and capricious; forgiving and vengeful; solicitous and callous; protective and genocidal.

The Judeo-Christian accounts of God’s dealings with humankind present a perplexing case study in Multiple Personality Disorder. For each admirable trait on display, we find its opposite: long-suffering and short-fused; judicious and capricious; forgiving and vengeful; solicitous and callous; protective and genocidal.

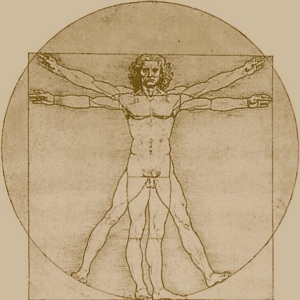

This all-too human catalogue could have been cited by my children to describe their father. And therein lies the question: When we conceive of Deity, how do we know God hasn’t simply become a projection of our own personalities–or the personalities of our sages and chieftains, our grandmothers and grade school teachers.

Natalie Goldberg writes of a priest friend of hers who quipped, “When your God hates all the same people you hate, you can be sure you’ve created God in your own image.”

In The God Who Weeps, Fiona and Teryl Givens argue that over the long course of history, not every conception of God has deserved our devotion. Setting aside multitudinous pagan gods, the authors dispense with conceptions of God held by Augustine, Luther, Jonathan Edwards, and others. A god with the characteristics of wrathfulness, vengeance, capriciousness, and violence, according to the authors, “do not deserve our reverence or our love,” and so the authors summarily reject conceptions of God that we moderns now find abhorrent. To this point I’m on board. Then they go on to say, “[This] does not mean we can simply choose the kind of god we want to worship . . . We cannot create gods that match our desires willy-nilly.” Maybe the operant phrase is “willy-nilly,” because in the remaining chapters they present a portrait of God that reflects their noblest sense of Goodness and Truth.

Is it possible that our personal conceptions of God reveal our own deepest natures? Some us will, Javert-like, envision a law-and-order God who demands justice and retribution; while others will, Valjean-like, imagine a God of boundless mercy?

The other day, my friend confided how, after suffering so long with feelings of inadequacy and not-belonging, she needs to believe that God is unconditionally loving and accepting. Nothing less will give her soul wings.

I know others who’ve been abused by men; for them, envisioning a male god poisons prayer and sabotages any hope for a meaningful relationship to Deity. Some have begun imagining a Heavenly Mother when they pray. The barriers to God’s love fall away. By giving themselves permission to imagine the God their heart needs, these women (and sometimes men) are able to tap into a well-spring of love and compassion.

I know others who’ve been abused by men; for them, envisioning a male god poisons prayer and sabotages any hope for a meaningful relationship to Deity. Some have begun imagining a Heavenly Mother when they pray. The barriers to God’s love fall away. By giving themselves permission to imagine the God their heart needs, these women (and sometimes men) are able to tap into a well-spring of love and compassion.

Do we fashion God from the clay of our own deepest need?

Another passage from The God Who Weeps proposes an argument for the existence of God that goes something like this: Since we find ourselves longing for God, it is fitting and proper that God would exist to satisfy that longing. I find this absolutely charming—as if the universe is obliged to respond to our cravings, to complement our desires with such perfect symmetry. Missing Piece, meet Big O.

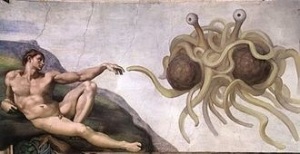

But which god exists? Are there not so many conceptions precisely because there are so many kinds of longing? And why would God manifest as a Flying Spaghetti Monster? What psychic projection brought a plate of pasta into existence? What craving conjured those noodley appendages? A million carb-starved Atkins dieters?

In How to Know God, Deepak Chopra proposes that God can be worshipped at many levels. Only as we ourselves progress and evolve to greater levels of spiritual maturity, do we intuitively reformulate our conceptions of God to fit our new dimension of spiritual awareness.

When I read Chopra’s stages, I sense my own soul’s journey. Notice how the God in each stage satisfies a deep need:

Stage One: God is the Protector to those who see themselves in danger. This fits a world of bare survival, full of physical threats and danger. This conception of God projects a being who is vengeful, quick to anger, jealous, and metes out rewards and punishments. Fear characterizes this relationship, and if God is appeased you may be protected from Divine threats, fate, nature, etc. You want to be on this God’s good side.

Stage Two: God is the Almighty to those who need control and power. This fits a world of power struggles and ambition, where fierce competition rules. This conception of God projects a kingly figure who is sovereign, omnipotent, just, impartial, rational, upholds law. Awe and obedience characterize this relationship, and if you maintain allegiance to God and honor Divine law, you will receive boons in the form of answered prayers.

Stage Three: God is Peace to those who have discovered their own inner world. This fits a world of inner solitude where reflection and contemplation are possible.This conception of God projects a being who is calm, consoling, undemanding, conciliatory, serene. A God of Peace is found through silent contemplation and meditation.

Stage Four: God is the Redeemer to those who are conscious of committing a sin. This fits a world where personal growth is encouraged and insights prove fruitful. This conception of God projects a being who is understanding, forgiving, accepting, inclusive, and tolerant. This God is known when a person achieves self-acceptance.

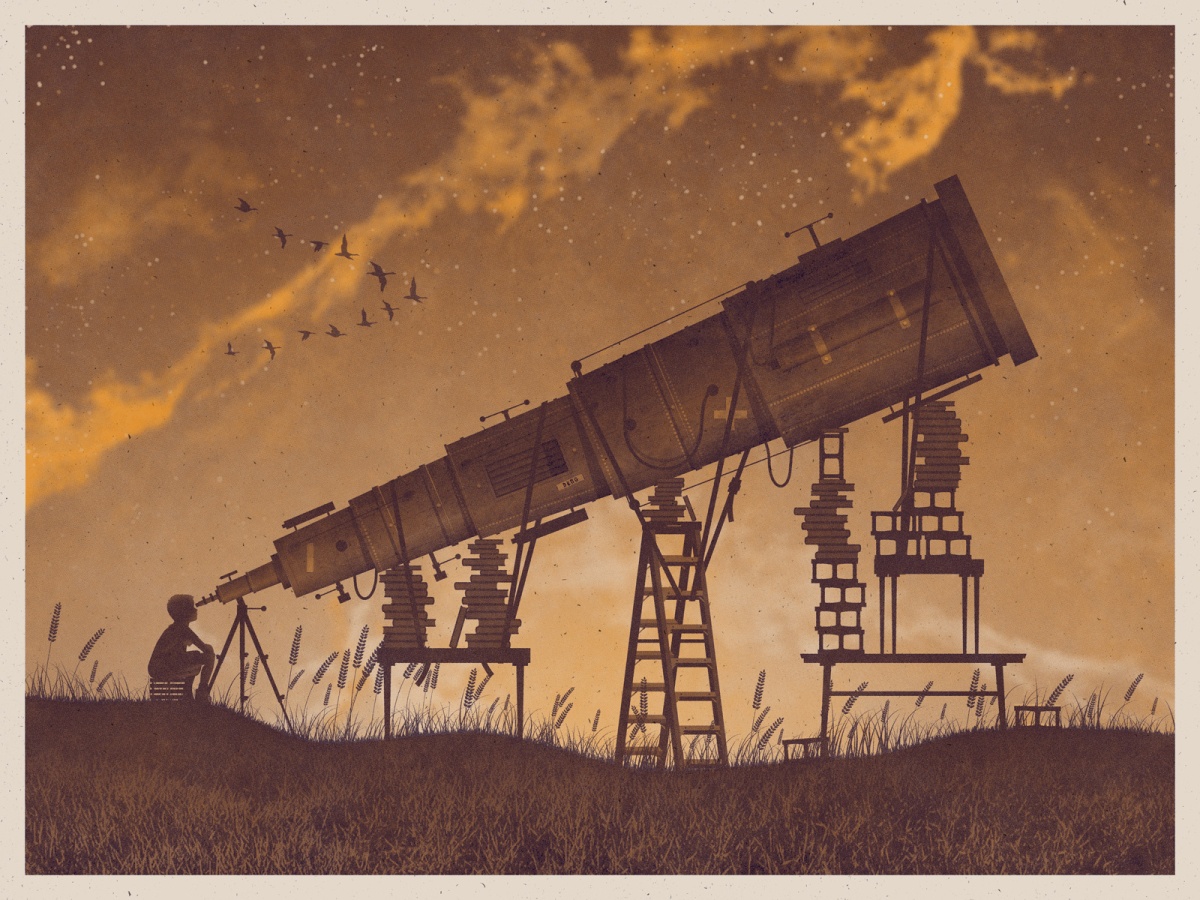

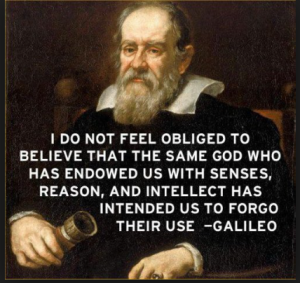

Stage Five: God is the Creator when we wonder where the world came from. This fits a world that is constantly renewing itself, where innovation and discovery are nurtured. This conception of God projects a being of unlimited creative potential, open, generous, abundant, willing to be known, and inspiring. This God is accessed through inspiration.

Stage Five: God is the Creator when we wonder where the world came from. This fits a world that is constantly renewing itself, where innovation and discovery are nurtured. This conception of God projects a being of unlimited creative potential, open, generous, abundant, willing to be known, and inspiring. This God is accessed through inspiration.

Stage Six: God works Miracles when we need the laws of nature to be revoked. This fits a world that contains prophets and seers, where spiritual vision is nurtured. This conception of God projects a being who is healing, magical, transformative, and mystical. This God is found through grace.

Stage Seven: God is a Pure Being (“I Am”) to those who feel ecstasy and a transcendent sense of pure being. This fits a world that transcends all boundaries, a world of infinite possibilities. This conception of God defies easy labels, being infinite, immeasurable, unchanging, unborn, undying, unmanifest, and intangible. Union with this God is found through transcendence.

I love this evolutionary framing, because it suggests that our conception of the Divine is only constrained by the capacity of our hearts. Perhaps, after all is said and done, we create God in the image of our own soul.

An Indian guru puts it like this:

“You believe that you were created to serve God, but in the end you may discover that God was created to serve you.”