In June 2014, our family moved to southern India to volunteer among leprosy-affected communities. We ended up spending almost a year there, providing basic hygienic care and dressing wounds, building latrines, combatting stigma and social isolation, alleviating poverty through micro-lending, and empowering children from the leprosy colonies through education and talent development.

It was our privilege to work alongside inspiring volunteers and committed staff in situations that called for our deepest compassion, and every day was an invitation to stretch far beyond our selves. My five children, aged from 19 years down to 8, earned my life-long respect for how they rose to the occasion; and Rebecca, of course, was amazing–a natural born Mother Teresa. I, on the other hand, spent most of the year attempting to piece back together the shattered fragments of a naively-held Messiah Complex that couldn’t survive even the first week intact. By the end of the year, I’d given up trying to be that person; instead, I began allowing myself simply to show up, vulnerable and open. The following essays, written while we were in India and gathered here chronologically, reflect that journey towards presence, learning to sit as one wounded among the wounded and discovering the miracle of wholeness.

Beep, Beep. We are Here.

. . . I’m shaken by this. Not our safety–it’s becoming increasingly clear that Rajendiren will expertly navigate these perilous waters–it’s the sense that here, with a billion plus people, life is cheap. Like ants crawling over ants to get to work. I know this is only apparent, but that’s how I’m feeling as we drive. A collective sense that the stream of traffic, that ravenous beast, must continue to flow, even if must be fed a few lives from time to time. Read More

A Tale Cut Short

. . . there’s some tumult in the kitchen. Rebecca points up in the corner near the fan vent. There’s a gecko, the size of a pinky clinging to the wall, panting. And where a tail should be, there’s only a stump. I know tails regenerate, but none of us hold out much hope for this little fella. Rebecca points out a gash from the fan blade on its torso.

“I saw it skittering into the vent and then . . . . chink . . . it skittered out without a tail.”

One of the kids says they think they saw it fall.

“Saw what?”

“The tail.”

“Where?”

They point at the counter-top space next to the gas burners. “There.”

We look.

It’s twitching.

It’s the size of a chow mein noodle, translucent, and it’s arcing back and forth like a miniature windshield wiper. Read More

I Meet “Mountain of Wisdom”

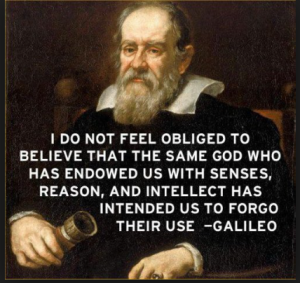

. . . “God in me, God in them. No difference,” he says.

I’ve read similar sentiments from Mother Theresa, but Vedadhri says it as if asserting water is wet. This wasn’t some theological article of faith, but a basic fact of the universe. I think how the same religious world view that justifies the stigmatization of leprosy as cosmic payback for some karmic misdeed in a previous life could also provide the insights motivating compassion and charity. Hinduism is no different than Christianity and Islam in this, it seems, with some of us beating swords into plough-shares and some sharpening those plough-shares back into swords, depending on how our heart is swayed by our scriptures. Read More

Right Hand, Left Hand

. . . A meme has been floating around Facebook, suggesting that we are God’s hands. I don’t whether that’s true. If it is, then about half of us must be God’s left hand. My service so far is mostly of the left handed variety: digging holes for toilets and septic tanks; dumping basins of water made foul by oozing ulcers; clipping toenails of feet on which only one or two toes remain; emptying our bathroom bucket of used squares of imported toilet paper; tearing off a piece of chapatti when no one’s looking; and killing scorpions in the middle of the night with the same sandals that I take off every morning at the door of the meditation hut where I wish all living beings peace. I’m okay with that. And every morning, with hands pressed together into a lotus bud to begin my prayer of peace, it’s the left hand that most feels the throbbing of my heart. Read More

Still Life: A Study in Green

. . . Cohen depending on the tooth fairy to find her way to India, which she does, unbelievably, three times already. Lifting the pillow and placing three 10 rupee notes under his sleeping head, each bearing the likeness of Gandhi who will bring dreams of peace. And already the new teeth pushing through, each emptiness filling, slowly. Somewhere between hole and whole.

And Stumpy our gecko, fan-blade survivor, depending on the voodoo of cell regeneration. The brown-green bud sprouting like an onion bulb into another tail, until we can’t tell him apart from any of the other geckoes we see skittering across our bedroom walls at night, or, unseen, hear snickering behind curtains in the evening as the kids form words in their nightly round of Banana Grams. Tile by tile, cell by cell. Forming and reforming.

A baby tooth is lost no sooner than a new one is ready to take its place. A tail reforms, faithful to the genetic specs printed in the DNA of every cell of the gecko’s body. Without searching, what is lost becomes found; without mending, what was rent becomes whole. When wood is green, it’s alive, supple, vigorous. Lop off the trunk and the sap bubbles up, heals the wound, feeds new branches.

I wonder at the resilience of life. And now, here in India one month, I think of the people at the leprosy colonies, what their leprosy has cost them. The pinnacle of evolution, and their DNA as Homo sapiens doesn’t provide a lizard’s worth of instruction on how to regenerate a toe, or how to return the club of a hand back into sophisticated digital technology. Read More

Cohen and I Spend the Morning Getting Buzzed at the Local Saloon

. . . Kumar’s scissors open and close, snick, snick, snick, in the same steady but unhurried way. Periodically he tilts Cohen’s head up back. A few young men step out of the street and into the saloon, pick up a spare comb from the barber’s grimy counter, and groom themselves in front of the mirror for a minute or two and then, as suddenly as they came in, they toss the comb back on his counter and step back out into the street. This happens twice more during Cohen’s haircut. I’m guessing they’d got haircuts from Kumar in the past, may have standing permission to come use his comb and mirror whenever they’re in the area. But seeing random people swooping in and sharing the same comb makes me a little uneasy, especially for a population where it’s not uncommon to see children and even some adults shorn to the scalp to rid themselves of nits. Ask me no questions and I’ll tell you no lice. Read More

What’s in the Bag?

. . . “What’s in the bag?” I ask.

Over the last couple of weeks I’ve pulled out of the bag a Tibetan singing bowl, a toothbrush, a Native American flute, a blister pack of Mefloquine (anti-malarial medicine), a pound of uncooked basmati rice, and a stainless steel tea cup. And every day the mystery leads us to a story and the story leads us to a lesson. Actually, the story IS the lesson.

Today, I’ve brought a snake. A life-size, weighted, coiled, realistically painted, rubber snake. Cohen brought it along to India with him because we allowed each child to bring one “comfort animal” on the plane with them. And he wanted to bring his snake. Not a problem in LAX, nor at Amsterdam, but when we tried to get through security to board our final leg from Delhi to Chennai you’d have thought the X-ray specialist pausing at Cohen’s backpack had discovered a nuclear detonator. Soon a military guard was interrogating us.

“What is in the bag?” he asked us.

“Um . . . lot’s of stuff. It’s our little boy’s carry on,” Rebecca sputtered. “Is there a problem?” Read More

Abraham’s Song

. . . I met Abraham in the Vandalore Leprosy Colony. He and I hit it off because we’re both musicians. I’d brought my Native American flute along, thinking it might be nice to play something soothing for the patients while their wounds were being treated by our medical team. I’m covering holes on the cedar flute with my fingertips, making up a melody, when Abraham steals the show. Now, I’ve studied the jazz art of improvisation in college, but this was improvistation in its truest form. Having no money for a proper instrument, and no intact fingers to play one with anyway, Abraham devised a way of humming while alternately plugging the stubs on his hand into his nostrils, as if pushing valves on a trumpet. The sound is, well, not exactly what you’d call beautiful, but I found myself entranced, snake charmed. Later, he took me to his home and banged on a plastic tambourine for me, singing full-throated. Pictures of the Virgin Mary floated along the walls. Read More

Sri Lanka, Part I: Mud and Mudras, Lotus and Dulip

. . . WHEN WE ARRIVE IN SRI LANKA, the first one to welcome us is the Buddha. I get the feeling he would have been just as content with us staying in India, but he doesn’t seem to mind that we’re here. He’s sitting in the lotus position, upturned soles resting on opposite thighs, gaze lowered. Passengers from our flight push past me, anxious to reclaim their baggage. I’m pausing, hoping to be rid of mine. A reverential spirit alights on the twig of my heart and then flutters away once I see the statue more closely. First I notice the pendulous lobes of the Enlightened One’s ears. They stretch so low he must have hung buckets of water from them as a boy, thus freeing his hands for gesturing. Which leads us to the second detail: the Compassionate One is flipping us off. Read More

Sri Lanka Part II: Climbing Up the Buddha’s Back with 400 Pounds of Poop

. . . They simply reasoned that if an elephant’s diet is mostly fiber, its poop must be, too. With that insight, the Mr. Ellie Pooh paper company was born. An employee gave us a tour of their factory, which borders the elephant sanctuary. The system goes something like this: They spread out the poop to fully expose it to the sun. Then they cook it, subjecting it to intense heat that sterilizes all the yucky stuff. What’s left is a slurry of fiber that’s dried over a screen, pressed smooth, cut, and sold to eco-conscious consumers at healthy profit margins.

Hearing the man talk about this process, I’m reminded of the Buddha’s most fundamental teaching, the 4 Noble Truths. The 1st Noble Truth? Poop happens! When we understand the nature of that poop and what it’s made of, we’ve arrived at the 2nd Noble Truth. Believing that we can transform that poop into something useful moves us to the 3rd Noble Truth. Then, following the path outlined in the 4th Noble Truth, we can bring sufficient energy to bear, transforming something stinky and toxic into something pure and productive. Read More

Divine Union: A Hindu-temple inspired reflection on twenty years of marriage.

. . . Large enough to make even the most confident of men more than a little insecure, the lingam symbolizes the god’s male potency and virility. But on this late afternoon, twenty years since Rebecca and I, twain, became one flesh, I can’t help but reflect on a temple symbol that foreigners often miss: Shiva’s lingam is always set in and circumscribed by a divine womb, or Yoni. It is only together, Yoni and Lingam, that the Divine is fully expressed. Read More

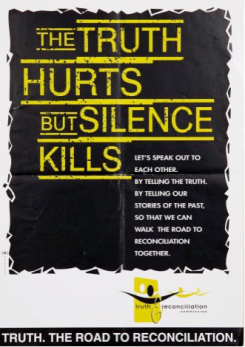

That’s Where the Light Enters

. . . If we’re lucky, we shed any silly notions that we (the supposed “whole”) are bringing healing to them (the presumed “broken”). We simply share a space where healing happens, and it happens as much to us as to them, though one of us wears a mask and one wears a wound. Healing becomes another name for wholeness revealing itself. Read More

Brooklyn leaves (with a Matriarchal Blessing)

. . . So here I share a poem I’ve written for Brooklyn, in which I imagine she finds herself quite unexpectedly visited by a goddess in the form of the fearless Durga, who has come to endow her with the courage and wisdom she’ll need as she continues conquering the world. Read More

A Few Notes Before We Leave . . .

. . . You seem like a very nice razor blade and I’m sure if we’d met under different circumstances, we would have hit it off handsomely. But see, I was next in line when the customer in the barber chair pulled off his t-shirt, lifted his right arm high into the air and grunted for Kumar to scrape his greasy pits with you. Read More

Vivid Dreams: A Valediction

. . . How much will stick? If I’ve come to recognize Jesus (or Infinite Worth or Buddha-nature) in the faces of the leprosy-affected, will I recognize it back home in the face of the grimy man holding a cardboard sign, the obnoxious neighbor, the surly skateboarder loitering in the school parking lot?

Obvious suffering engenders compassion–and in this way, serving the leprosy-affected required from me no special force of will–but how do I respond when someone triggers my contempt, my revulsion? Already, I have to admit, back in Gate C-19 waiting to board, my small self, the smug, disconnected ego self, was chiming in with snide remarks about that passenger who could have been from Duck Dynasty. I caught myself feeling smarter, more sophisticated, more enlightened than him. And so I shrunk by just exactly that much. Read More