Postcards from a Spiritual Journey: Introduction

Postcard #1 I’m finding goodness from many sources

Postcard #2 I want to see the whole elephant

Postcard #3 There are many paths up the same mountain

Postcard #4 I sense that feeling the Spirit is a universal, not exclusive, gift

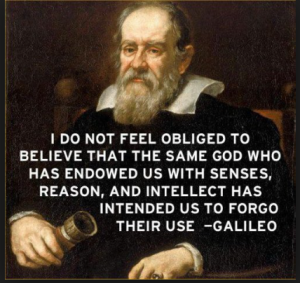

Postcard #5 My faith doesn’t obligate me to believe anything that isn’t true.

“Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth.” – Pope John Paul II

FAITH CONTINUES TO BE A BEAUTIFUL and animating force in my life. I’m not one of those who feels contemptuous of anything that can’t be proven; the things I value most are, by nature, subjective: the love I feel for my family, the sense that my life has purpose, a belief in the worth of every person. These are things I hope are true, and I choose to live accordingly.

Let’s be honest, we live in a world in which many things can neither be proven nor disproven through the faculties of reason. A spiritually vibrant life, in which faith propels us forward, allows us to sail the seas of uncertainty, to navigate the unknowable.

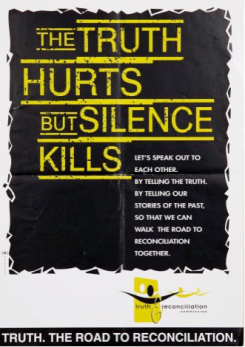

But some things can be known. Some claims can be tested.

When it comes to investigating religious claims—particularly those truth claims upon which we have built our lives—we tend to have some trepidation. Few of us could say, as Thoreau, “Be it life or death, we crave only reality. If we are really dying, let us hear the rattle in our throats.”

If I’m committed to truth, it means I must be willing to look, in an honest, unflinching way, at the very foundations of my belief. “If we have the truth, it cannot be harmed by investigation,” J. Reuben Clark said, “but if we have not the truth, it ought to be harmed.” I agree with Clark, but I also acknowledge that what we call belief is actually a composite of many beliefs—some sound and others based on false assumptions. I am learning to uproot the false, without also tearing out the true.

In this, I’m inspired by sincere seekers of truth such as Henry Eyring, the world-renowned Mormon scientist. He displayed the true scientist’s trait of openness to new ideas and an ability to cast aside old theories if they no longer proved faithful to new data; likewise, he displayed the true spiritual seeker’s trait of openness to new ideas and an ability to cast aside commonly-held beliefs (or even scriptural accounts) if they were contradicted by reliable and compelling evidence. His own father gave him permission to approach any of the Church’s teachings that way:

“In this church,” he told the young man as he was leaving for college, “you don’t have to believe anything that isn’t true.”

I no longer cower behind faith as an excuse for ignoring, suppressing, or denying information that may challenge my current beliefs. Faith may fill in the blanks when not all evidence is available, but more often than that, my faith plays a more positive, active role. My faith fills me with courage to face difficult issues. And to the extent that we must all “see through a glass darkly,” faith allows me to move forward, trusting my feet to find the way.

When we are told by leaders not to look closely at an issue, but instead to doubt our own ability to discriminate between truth and error, I wonder if we are really being invited to exercise faith, after all. It is precisely because I have faith that I am willing to examine problematic issues. The avoidance-based approach only dulls my soul. If I want to truly awaken, I must stop humming the lullaby of certainty to myself.

When I occasionally feel discouraged by the contempt some in the Church express towards independent thinking, I remind myself that the impulse to challenge the prevailing wisdom is not a failing, but an admirable trait, as Hugh B. Brown pointed out to young college students in the 60s. I’ll close this Postcard with his words ringing in our ears, an anthem to faith:

I admire men and women who have developed the questing spirit, who are unafraid of new ideas as stepping stones to progress. We should, of course, respect the opinions of others, but we should also be unafraid to dissent—if we are informed . . . We should be dauntless in our pursuit of truth and resist all demands for unthinking conformity.

P.S. I have written a piece on intellectual freedom and the tension between an undaunted spirit of inquiry and institutional insecurities. Here’s the post.